In this second of her three blog articles, Anne Strathie – author of A History of Polar Exploration in 50 Objects: From Cook’s Circumnavigations to the Aviation Age – writes about a rare and fascinating photograph album in Hull Maritime Museum’s collection. The album, dating back to 1880, provides insights into little-known but important privately-funded Arctic expeditions which had repercussions in relation to polar exploration history and, more surprisingly, the world of literature.

Benjamin Leigh Smith’s ‘Eira 1880’ photograph album

By the late 19th century, Naval officers, whalers and sealers regularly headed to polar regions in large-scale customised vessels. But smaller, privately-funded expeditions also played an important role in polar exploration history. Two such were undertaken by Benjamin Leigh Smith, a copy of whose ‘Eira 1880’ photograph album is in Hull Maritime Museum’s collection (ref. 2005.5367) and provides an insight into his expeditions to Franz Josef Land, which, like Spitsbergen, was regarded as a potential ‘gateway’ to the North Pole.

In May 1880 Leigh Smith left Peterhead, Aberdeenshire, on his brand-new steam-yacht Eira. Local whaling-master David Gray of Peterhead had designed and supervised the construction of the new steam-yacht – one he and Leigh Smith believed was capable of reaching the North Pole. As Leigh Smith headed for Spitsbergen he encountered David Gray and his brother John in their own, larger vessels Hope and Eclipse. After the Grays moored alongside Eira, they came aboard to give Leigh Smith important news – that pack-ice north of Spitsbergen was so impenetrable that Leigh Smith should avoid that area and head for Franz Josef Land instead.

That evening, Leigh Smith entertained the Grays and their ships’ doctors to dinner. In the late evening ‘gloaming’ Arctic veteran photographer William ‘Jonny’ Grant photographed the three ships’ captains, Eira’s ice-master and the three ships’ doctors. As Leigh Smith’s guests left Eira to return to Hope and Eclipse he, his ship’s doctor Dr William Neale and Eira’s ice-master William Lofley wished the others ‘safe travels’ and – in the case of 21-year-old Arthur Doyle – good fortune with his continuing medical studies in Edinburgh.

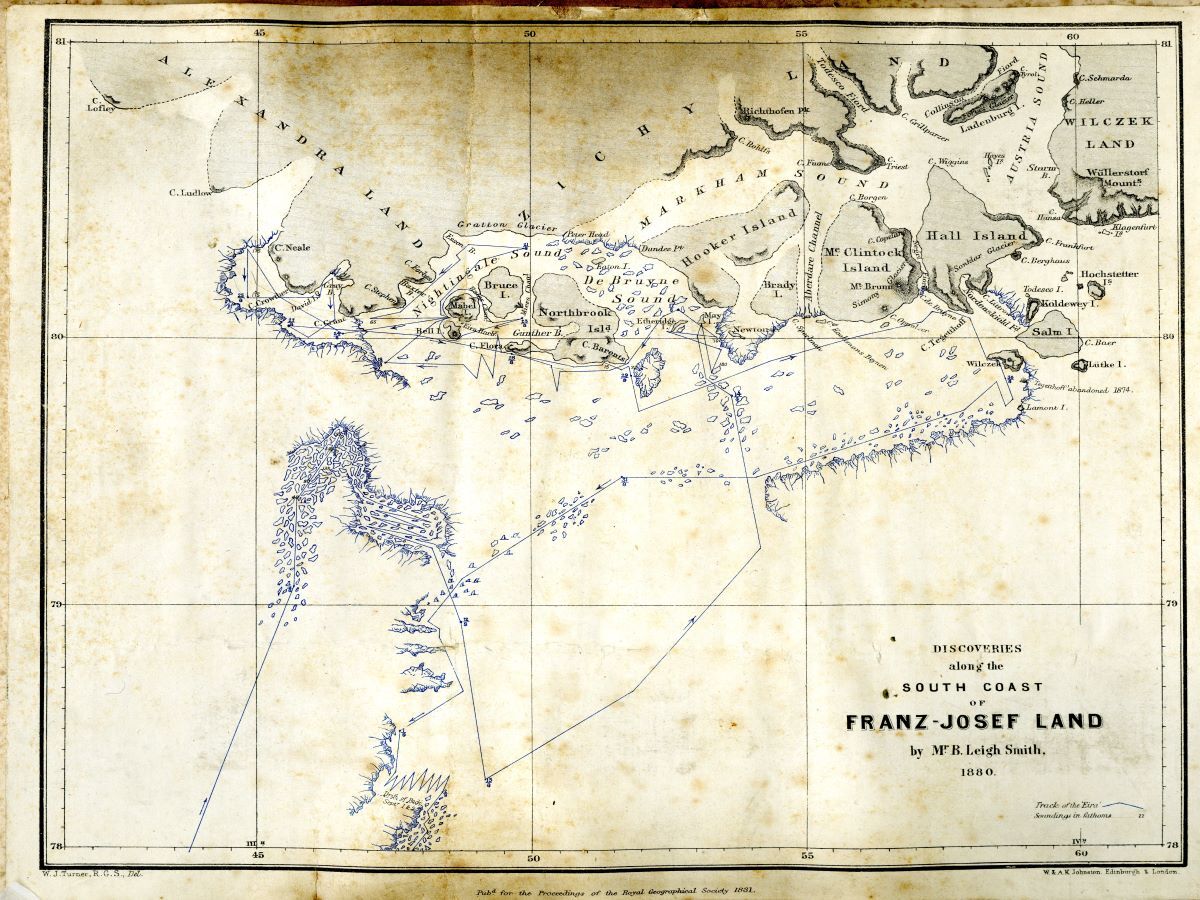

Following this fortuitous encounter, Leigh Smith continued to Franz Josef Land, where he and his men lived on Eira while they built shelters at ‘Cape Flora’. That done, they began exploring and charting the region – one in which, Leigh Smith discovered, it could be difficult to distinguish between ice-covered land and the heavy pack-ice some whalers and explorers believed continued to the North Pole.

On returning to England, Leigh Smith offered his charts and other material to the Royal Geographical Society in London. The society’s ever-energetic Secretary, Clements Markham, was impressed by Leigh Smith’s work and offered to assist Leigh Smith and Neale to produce a formal report for submission to RGS Council members.

A few months later Leigh Smith learned from Markham that he was to be awarded the Royal Geographical Society’s prestigious Patron’s Medal for his work on and around Franz Josef Land. A very private man who sought neither publicity nor fame, Leigh Smith asked Markham to collect the medal on his behalf.

In June 1881 Leigh Smith returned to Franz Josef Land to continue his work. That summer’s pack-ice was even more perilous and unpredictable and – following a sudden change of tide – eventually began crushing Eira. After his beloved ship was punctured by ice and sank, Leigh Smith and his men had no alternative but to overwinter in their shelter on Cape Flora.

Leigh Smith and his men endured a hard winter, during which long hours of darkness, freezing snow-storms and ferocious gales were occasionally enlivened by awe-inspiring aurora. In June 1882 as the ice began breaking up, they began dragging and rowing their auxiliary boats until they reached more open water. When they finally reached Novaya Zemlya (where Leigh Smith knew whalers gathered) they were surprised and delighted to recognise the Gray brothers’ vessel Hope – which, they learned, Clements Markham and other concerned friends and relatives had commissioned to search for them.

As with his previous expedition, Leigh Smith sought no acclaim or awards, but the ripple effects from his expeditions on Eira were considerable.

In the early 1880s, Leigh Smith’s erstwhile dinner guest on Eira – now Dr Arthur C. Doyle – wrote a short story, The Captain of the Pole Star, based on his time as ship’s doctor to with the Grays. Following a decade combining his medical duties with further writing Dr Doyle had become better known as ‘A. Conan Doyle’, creator of detective Sherlock Holmes and his assistant Dr John Watson. In writing about the latter, Doyle drew on his medical experience, while illustrations of the fictional detective sometimes showed him wearing a deer-stalker hat and smoking a hooked pipe – not dissimilar to those sported by Dr William Neale, Eira’s ship’s doctor, on board Eira in 1880.

In terms of polar exploration history, Leigh Smith’s charts of Franz Josef Land and surroundings were taken north in 1893 by Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen. The Norwegian explorer (already well-known for having crossed Greenland on skis) planned to drift across the North Pole on his new ship, Fram. In summer 1895, as the frozen-in Fram began veering away from the Pole, Nansen and Hjalmar Johansen left the ship and set out on skis, with dog-sledges, in hopes of reaching the Pole across the ice.

In October 1895 Nansen and Johansen set a new Farthest North, but by then the current-borne pack-ice was carrying them south as fast as they could ski north. They abandoned the unequal struggle and, armed with Leigh Smith’s charts, headed for Franz Josef Land, in hopes of finding shelter or provisions left by Leigh Smith or others. In June 1896, as the two men neared their goal, Nansen was delighted to encounter another British explorer, Frederick Jackson, who was exploring the archipelago using Leigh Smith’s charts.

Jackson welcomed the exhausted pair to his spacious expedition base.

After they recovered from their ordeal and Jackson’s relief vessel Windward arrived in late July (with supplies for Jackson’s next season), the two Norwegians were able to travel back to Norway’s northernmost settlements, where they were warmly welcomed by cheering crowds.

In late August, thanks to his friend George Baden-Powell and his yacht Otaria, Nansen was finally reunited with his expedition ship Fram in Tromsö.

By September images of the meeting of Jackson and Nansen – like those of David Livingstone and Henry Stanley in Africa in 1871 – were adorning the front pages of magazines in Britain, Norway and far beyond.

Nansen was now arguably the world’s most famous living explorer. In March 1897, during an extensive lecture tour of Britain, he visited Hull’s Assembly Rooms where the evening’s chairman recalled Hull’s proud Arctic history (including Captain Humphrey’s rescue of the Rosses) and close links to Norway. Nansen regularly acknowledged, including on stage, the assistance of Jackson, Baden-Powell and Leigh Smith. The previous month, following publication of his expedition report Farthest North, he had also sent a copy to Leigh Smith with a personal dedication thanking him for his ‘excellent [charting] work in Franz Josef Land.’

A History of Polar Exploration in 50 Objects: From Cook’s Circumnavigations to the Aviation Age is published by The History Press - more info.