In her third and final blog article, Anne Strathie – author of A History of Polar Exploration in 50 Objects: From Cook’s Circumnavigations to the Aviation Age – focusses on two Hull-based mariners – William Colbeck (1871-1930) and Alfred Cheetham (1868-1918).

Between them, the two men served in all major British Antarctic expeditions between 1895’s International Geographical Congress in London and Shackleton’s 1914-6 Endurance expedition. After Colbeck went south with the Southern Cross expedition (1898-1900), both men served in Scott’s 1901-4 Discovery expedition. Cheetham then went south three more times. Codas to their shared story include a lesser-known 1929-31 expedition on Discovery and the erection of a plaque in Hull’s Paragon Station in 2016.

The intertwined Antarctic careers of Hull mariners William Colbeck and Alfred Cheetham

In 1895, an International Geographical Congress was held in London under the chairmanship of Clements Markham, President of the Royal Geographical Society. As by then explorers such as Norway’s Fridtjof Nansen and America’s Robert Peary and Frederick Cook were closing in on the North Pole, delegates passed a resolution stating that ‘the exploration of the Antarctic Regions is the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken’.

In 1898, Markham and colleagues from the RGS and other British organisations were still planning and trying to raise funds for a two-ship ‘official’ British expedition. Markham was therefore rather taken aback when Southern Cross – captained by Anglo-Norwegian explorer Carsten Borchgrevink and financed by British newspaper proprietor Alfred Newnes – sailed for Antarctica. On board as navigator and magnetism expert was William Colbeck of Hull, a merchant mariner and Royal Navy reservist.

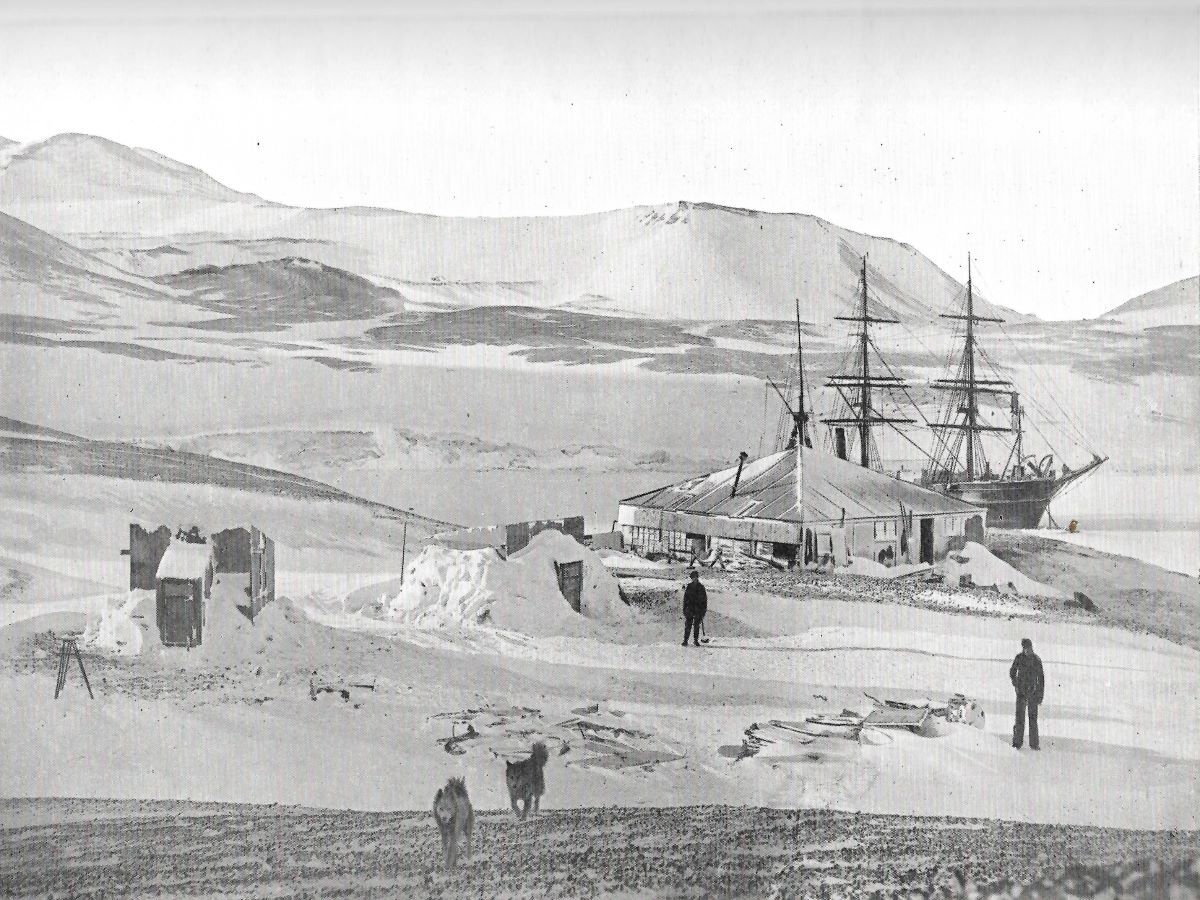

In early 1899 Colbeck, Borchgrevink, physicist Louis Bernacchi and seven others were deposited on Cape Adare in northern Victoria Land, armed with charts made by James Ross during his 1839-42 circumnavigation on Erebus and Terror. Before Southern Cross retreated to safer, ice-free waters to overwinter, Borchgrevink and his companions erected sturdy, pre-fabricated ‘winter quarters’ – the first recorded man-made habitation on the Antarctic continent.

During the long dark winter months at Cape Adare, Colbeck and Bernacchi worked closely together, including on magnetic readings and updated Ross’s estimate of the location of the South Magnetic Pole. In January 1900 – later than anticipated – Southern Cross broke through thick pack-ice to within reach of Cape Adare and managed to retrieve Colbeck and his companions.

Although Ross had failed to find a place to land, parts of the barrier had broken up or retreated, allowing Colbeck, Bernacchi and others to land, sledge south along the barrier’s top and establish a new ‘Farthest South’.

By the time Colbeck and Bernacchi (now firm friends) returned to Britain, Clements Markham had raised sufficient funds to pay for the construction of RRS Discovery. The ship, designed both for exploration and science, was expensive and, lacking sufficient funds to purchase and man another ship, it was agreed that Discovery would sail alone under Lieutenant Robert Scott RN. Bernacchi had found his winter on Cape Adare difficult, but agreed to join Scott’s scientific team. Colbeck, preferring to resume naval duties, would captain of the expedition’s relief ship Morning, which would sail south a year after Discovery, carrying provisions, equipment and everything Scott might need for a second season in Antarctica.

When Morning reached Cape Adare in early 1903, Colbeck found a note from Scott confirming that he planned to base himself in McMurdo Sound, near to the ice-barrier. Continuing south, Colbeck found another note at Cape Crozier indicating Discovery’s precise location. But as Morning approached the designated meeting place, Colbeck was confronted by miles of impassible pack-ice. He fired rockets to alert Scott’s men to Morning’s arrival, then began arranging to transport provisions and other items across the ice on sledges to the hemmed-in ship.

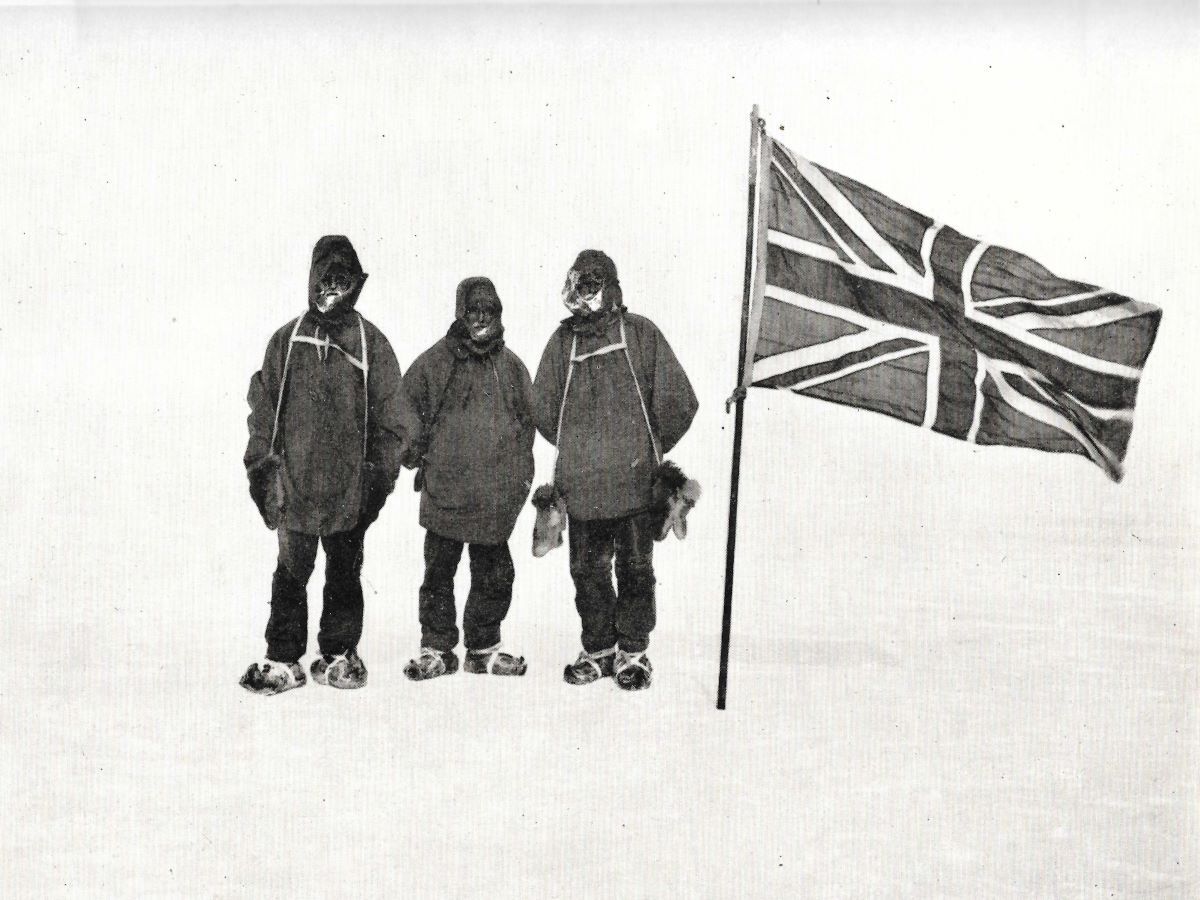

Although there was little sign of the ice around Discovery breaking up, the news from Scott and his men was otherwise good. Men had explored and charted the area thoroughly and identified glaciers leading to a high plateau – the likely location of the South Pole. In late 1902 Scott, Dr Edward Wilson and Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton had sledged across the ice barrier to a new Farthest South just beyond 82°S – some 200 miles further than Colbeck, Bernacchi and their companions had reached. Scott had hoped to reach 85°S, but by then all three men were exhausted, hungry and showing symptoms of scurvy.

Since then they had largely recovered, but the expedition doctors and Scott were concerned for Shackleton’s health should he have to remain another year. Colbeck agreed to take Shackleton back to New Zealand (where he could receive further treatment) and that Lieutenant George Mulock of Morning would join the landing party.

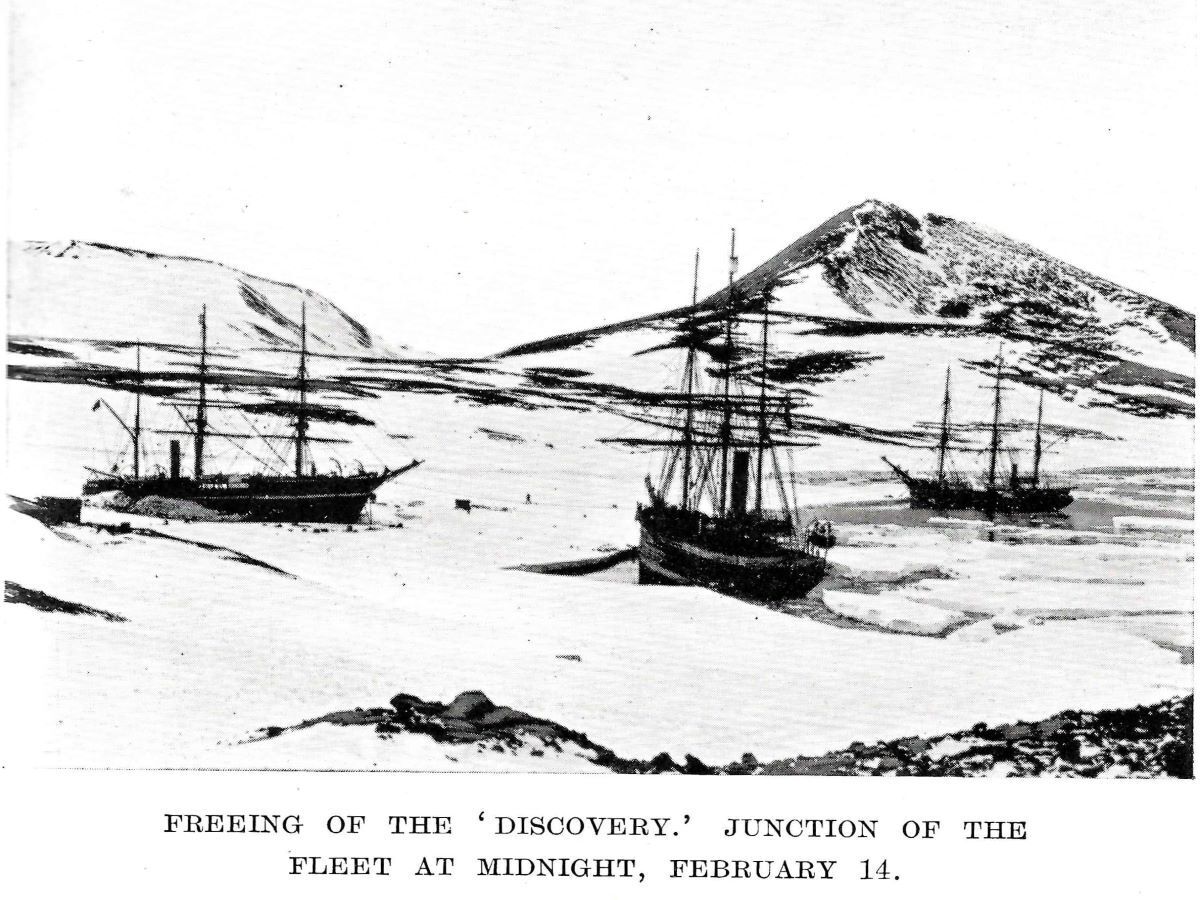

Back in New Zealand, Colbeck still half-expected that Discovery might return from the south under her own steam. When she failed to do so, he took Morning south again, this time accompanied by Terra Nova, a sturdy Dundee-built whaler, whose captain, whaling master Harry McKay, had long experience in Arctic ice. When the two ships arrived, Discovery was still hemmed in, but following weeks of battering, hacking, sawing and dynamiting the recalcitrant ice, Colbert and McKay freed Scott’s ship.

The service Colbeck and his men rendered to the Discovery expedition was recognised by the award of new-style polar medals. Colbeck also received a Royal Geographical Society medal and a silver globe for his efforts but decided that, following back-to-back Antarctic expeditions, he would rejoin his previous employers, Thomas Wilson of Hull. Several of Colbeck’s Morning shipmates, however, decided to return south.

One of Morning’s officers, Lieutenant Edward ‘Teddy’ Evans, began planning his own expedition, while Hull-based boatswain Alfred Cheetham signed up for Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition. This also gave Cheetham the chance to serve alongside Discovery veteran Frank Wild – who, during the Nimrod expedition had joined Shackleton and Eric Marshall on a southern journey which resulted in a new ‘Farthest South’ only 100 nautical miles from the Pole.

Shortly after Shackleton returned, Scott agreed to return south with a view to both reaching the South Pole and continuing his scientific and exploratory work. As Discovery was not available, Terra Nova was purchased for the expedition. Cheetham signed up for his third expedition, this time sailing with Morning’s Teddy Evans (who had joined forces with Scott) and Discovery veterans including Edward Wilson, Tom Crean, Patrick Lashly and Edgar Evans. In 1913, following Terra Nova’s return, Cheetham received a silver polar medal to add to his bronze medal and clasp from his previous expeditions.

Although the deaths of Scott, Wilson, Edgar Evans, Lieutenant Henry ‘Birdie’ Bowers and Captain Lawrence Oates cast a pall of sadness over Cheetham’s third expedition, Cheetham barely hesitated when Shackleton announced plans to cross Antarctica from the Weddell Sea to McMurdo Sound.

Shackleton’s Endurance expedition was even more exciting than Cheetham anticipated. When they left London in August 1914, Britain was on the brink of war. By early 1915 Endurance was stuck firmly in pack-ice which was drifting inexorably away from the Antarctic coast where they had planned to land. After Endurance was crushed and sank beneath the ice, Cheetham and his companions dragged auxiliary boats to the ice-edge and endured a perilous voyage to remote, inhospitable Elephant Island. As they were far from any shipping routes, Shackleton left with a smaller group (including Cheetham’s friend Tom Crean) on James Caird, in hopes of reaching South Georgia and obtaining help.

Wild (now in charge on Elephant Island), Cheetham and their companions tried to stay cheerful, stick to routines and survive on meagre rations. When Shackleton, Tom Crean and other rescuers finally reached Elephant Island in August 1916, Cheetham and his companions learned that the war which had broken out two years previously was still raging. Cheetham, like other Endurance expedition veterans, signed up for naval and other war duties.

Sadly, having survived two testing years in Antarctica, Cheetham died in August 1918, when his ship Prunelle was torpedoed by a German U-boat in the North Sea. His erstwhile Morning commanding officer William Colbeck had worked with London merchant shipping company during the war. He was more fortunate than Cheetham and rose to become a founder member of the Honourable Company of Master Mariners.

Colbeck kept in touch with his Antarctic shipmates, however, and in 1930 was elected President of the Antarctic Club, a blanket organisation open to members of all expeditions. Sadly, Colbeck died later that year – but by then his son William had joined an Antarctic expedition on Scott’s Discovery.

Many of those with whom William Colbeck jnr was travelling would have known to his father, Alf Cheetham or both. Young William’s expedition leader was Douglas Mawson, who had first travelled south on Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition. Frank Hurley, the expedition’s photographer and filmmaker, had played the same role on Mawson’s 1911-14 Aurora and Shackleton’s 1914-6 Endurance expeditions. Lead scientist James Marr also had previous Antarctic experience, in his case thanks to travelling, as a boy scout, along with Frank Wild and other Endurance expedition veterans, on Shackleton’s 1922 Quest expedition.

Although Colbeck had gone south first, Cheetham had, since they travelled together on Morning, become one of the few men to hold four polar medals and/or clasps. The only man who held more was Cheetham’s Endurance shipmate Frank Wild, who served on five expeditions. Both men are commemorated in London as well as Hull’s Paragon Station plaque, Colbeck on a plaque at the site of his former home in Lewisham, Cheetham on the Merchant Naval Memorial at London’s Tower Hill.

A History of Polar Exploration in 50 Objects: From Cook’s Circumnavigations to the Aviation Age is published by The History Press.